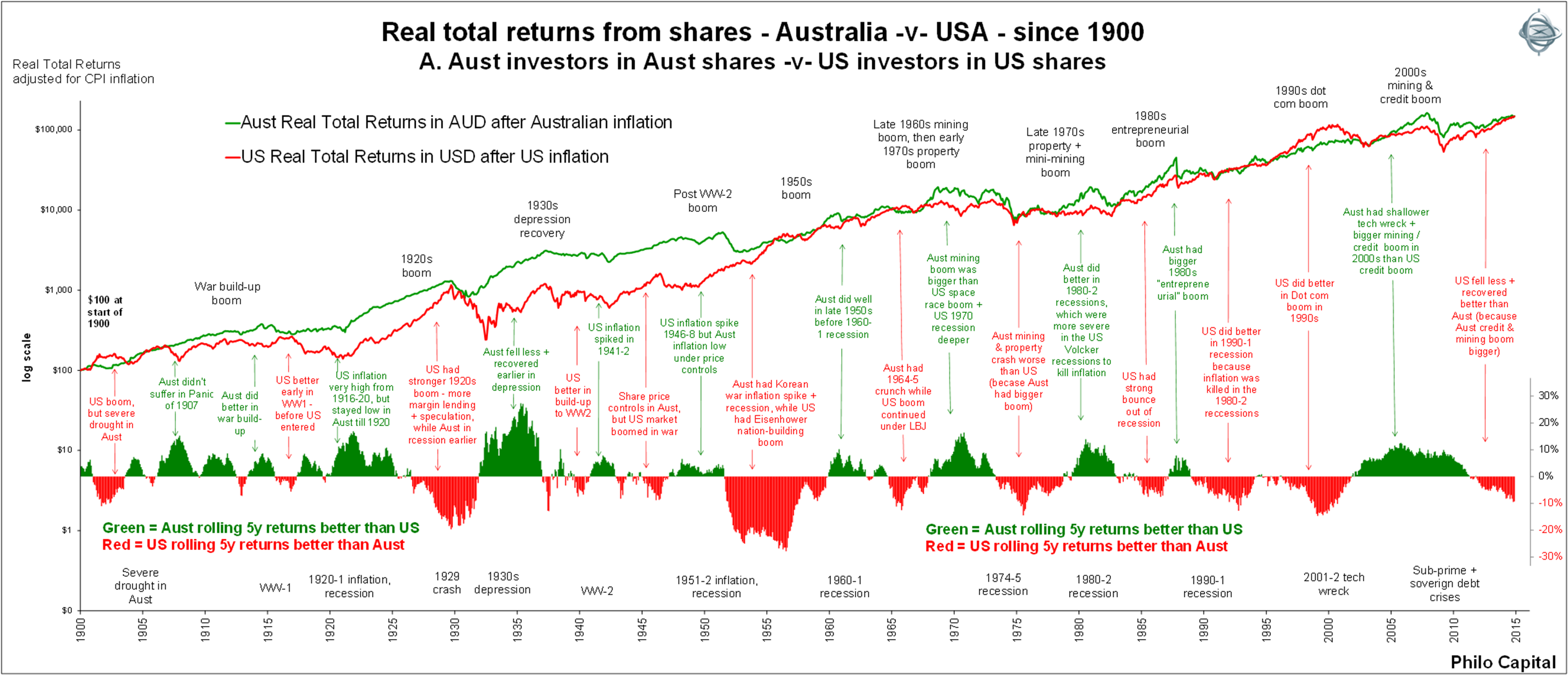

I am often asked how returns from shares have compared between the stock markets in Australia and the US. This topic came up again in a Cuffelinks story from last week so I have updated one of my favourite charts. It shows total returns (including reinvested dividends) after inflation from Australian and US stock markets since 1900.

Specifically, the first chart shows real total returns from the broad Australian stock market in Australian dollars after Australian CPI inflation (the green line) versus real total returns from the broad US stock market in US dollars after US CPI inflation (red line). Thus it compares how Australian investors have fared from their local Australian market in their local currency after local inflation, versus how American investors have fared from their local market in their local currency after local American inflation.

Therefore this compares the returns from the point of view of two different investors: an Australian in Australian equities versus an American investor in US equities. (In Part 2 we look at whether Australian investors would have done better investing in Australian shares rather than in American shares).

(This graph can be enlarged by clicking on it).

Returns the same from both markets since 1900

The above chart shows total returns to Australian investors has been virtually the same as American investors have received (in local markets, currencies and inflation). A$100 invested by an Australian investor at the start of 1900 would have turned into A$148,000 today (end of October 2014) and US$100 invested by an American investor in US stocks would be worth about US$148,000 today.

For American shares we use the S&P500 index with dividends re-invested, and for Australian shares we use the All Ordinaries index (and its predecessors) with dividends re-invested. These returns are before tax and brokerage costs. Tax rates and tax rebate regimes have changed many times in each country, and tax benefits from franking in the Australian market since 1987 would probably be more than outweighed by the impact of buy-backs in the US market. We also assume investors have been ‘long-only’ in each market. That is, they have not used margin lending or any other type of gearing or derivatives that wiped out many investors in the more extreme booms and busts along the way. It also assumes investors don’t panic buy in booms, nor do they panic sell in busts. They just hold on, re-investing dividends and adjusting holdings to stick with the index weights of each company.

Alternating booms and busts

Although the total returns have been same, there have been large differences for long periods at a time. Australia and America have taken turns at having bigger booms and bigger subsequent busts.

The lower section of the first chart shows the difference between rolling five year returns. This neatly illustrates how the pendulum has swung between Australian shares beating US shares (green vertical bars above the line in lower section), and US beating Australian shares (red vertical bars below the line).

The green and red text boxes across the middle of the chart highlight the booms and busts:

- In every second cycle the Australian market did better than the US market (green boxes).

- But between each of these periods the US market did better than Australia (red boxes).

Working backwards over time we see this pattern repeated throughout the past century:

- In the most recent big boom during 2003-2007, the Australian stock market generated higher returns than the US market because Australia had both a credit boom and a mining boom at the same time.

- The US didn’t have such a big 2003-2007 boom so the US didn’t have as far to fall, and has done better than Australia since the 2008-2009 bust.

- However the US market did much better in Australia in the late 1990s ‘dot-com’ boom, but it subsequently fell further than Australia in the 2001-2002 ‘tech wreck’.

- Following the same pattern, the Australian market did much better in the 1980s ‘entrepreneurial’ boom, but then fell further in the 1987 crash that followed.

- Further back, Australia did much better in the early 1980s recession, because the US was hit with the full ‘Volcker’ double dip recessions to kill inflation. Australia rejected monetarism and instead relied on the ‘Accord’ process to partially control inflation, and did not have the big inflation-busting recession until a decade later (Keating’s ‘recession we had to have’) in 1990-1991, when US shares did better.

- This pattern where Australia and the US took turns to have a big boom followed by a big bust goes all the way back for more than a century – even through world wars, recessions, the depression, inflation spikes and political crises – and each is noted on the chart.

- The biggest bust in the Australian market was in 1973-1974 (worse than the 2008-2009 GFC). It came after a double-barrelled boom – a speculative mining boom in the late 1960s followed by a speculative property bubble in the early 1970s. The Australian market rose higher than the American ‘space race’ boom at the same time, but then had further to fall.

- Further back still, the 1920s boom was much bigger in the US, fuelled largely by US margin lending and speculation. Australia did not have the same penetration of margin lending and was already in recession in the late 1920s well before the 1929 crash. Because the US boom in the 1920s was much higher, it crashed further.

- This pattern of baton-changing extended back even before 1900. Before the ‘panic of 1907’ in the US, Australia had a larger 1880’s boom because it was not just a banking/property boom but a mining boom as well. Consequently our early 1890s property and banking collapse was worse.

Given the remarkable consistency of this pattern, it is tempting to say that, because the last boom/bust was bigger in Australia than the US (the 2003-2007 boom and subsequent 2008-2009 bust), it is America’s turn for the next big boom/bust. Only time will tell.

Structural similarities and differences

The fact that both markets have generated similar returns from their stock markets over long periods is no great surprise. There are some important similarities but also some key differences.

Both are pluralist democratic former British colonies with relatively strong political, administrative, social and judicial institutions, rule of law and protection of private property rights, civilian control of the military, and both economies have grown by a little above 3% per year over the past century. Importantly, both countries have managed to stay out of destructive all-out wars against foreign powers on their own soil, and both have also avoided revolutionary changes in power and wholesale confiscation of private assets.

One key difference is the source of economic growth. Only one-third of American economic growth has come from population growth (more people producing the same output per person) while two-thirds of the growth has come from productivity growth (more output per person), but it has been the reverse in Australia. Two-thirds of Australian economic growth has come from population growth (more people doing the same old things), while only one-third of the growth has come from productivity growth (doing things better per person).

Difference in sources of returns

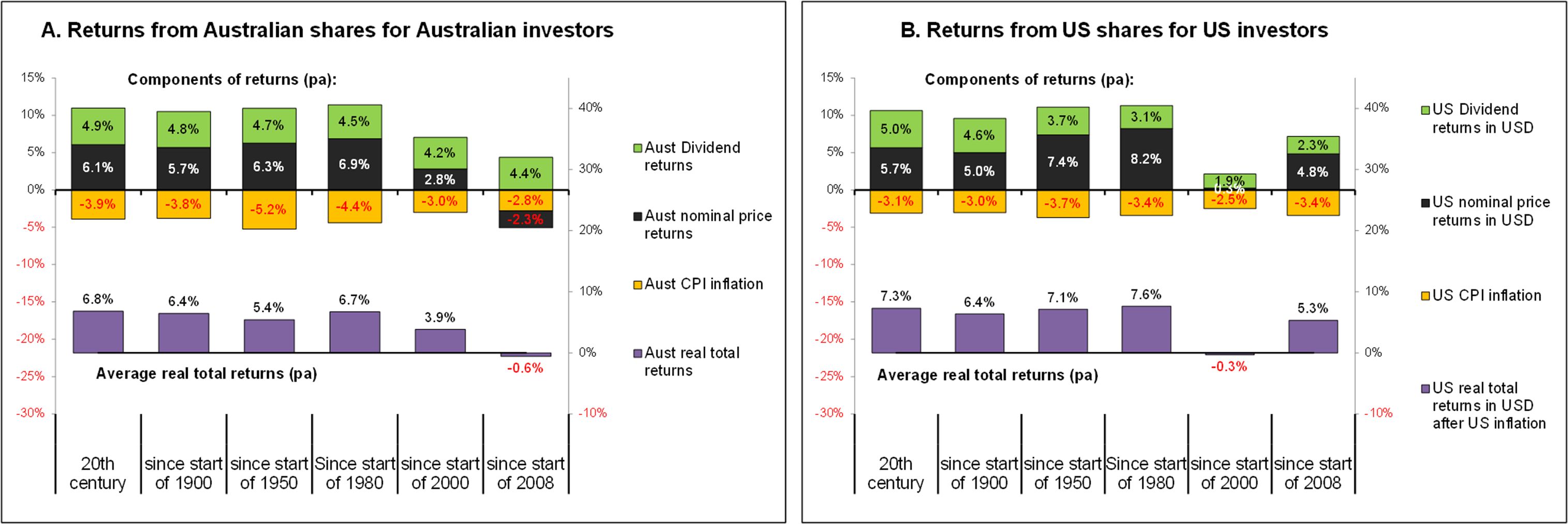

Another difference is the components of returns. The following two charts show returns from Australian shares (left chart) and US shares (right chart) broken into their component parts: dividends, price growth and inflation.

The purple bars on the lower section of the charts show total real returns over various periods. Both markets have generated total real returns of around 6% to 7% per year averaged over very long periods.

However, Australian companies have generated higher dividends and higher nominal price growth but Australia has suffered higher inflation. Higher dividends are a function of our market being a couple of hundred years younger than the American market. In younger markets investors demand quicker returns and allow boards to retain less for future growth. (In the US market’s first century US companies also generated near 100% dividend payout rates, much like Australian companies did in the Australian market’s first century). More recently, since 1987, the existence of franking credits on dividends in Australia has also led to higher dividends and less re-investment of earnings. In recent years the market structure in the US has favoured share buy-backs which have contributed an additional 2% to 4% to dividend returns (far exceeding the benefit of franking credits on Australian dividends, which has added around 1% to 1.3% to returns).

So to answer the question: “Which market has generated higher real total returns for local investors?”, the answer is: “It’s a dead heat” - although there has been a consistent pattern of the pendulum swinging between Australia and the US for more than a century.

Part 2 of this story will consider whether Australian investors have received better returns from the Australian or US market after accounting for differences in inflation rates and exchange rates.

Ashley Owen is Joint CEO of Philo Capital Advisers and a director and adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund. This article is for general educational purposes and is not personal financial advice.